One of the initiators of The Voice is Osaren Igbinoba, who fled from Nigeria to Germany in the early 1990s. Initially, he was housed in a reception centre in Mühlhausen, formerly Russian barracks.* As a former political human rights activist, the social isolation and inability to take political action affected him so much that he began to campaign for the rights of refugees in East Germany.

In October 1994, he founded The Voice Africa Forum with three other men from Nigeria and Liberia. Together, they tried to make people in refugee shelters in Thuringia aware of their situation and to motivate them to join forces to enact change.* Their commitment did not come out of the blue - after all, they themselves had been persecuted in their countries for campaigning for human rights and democratic participation there.

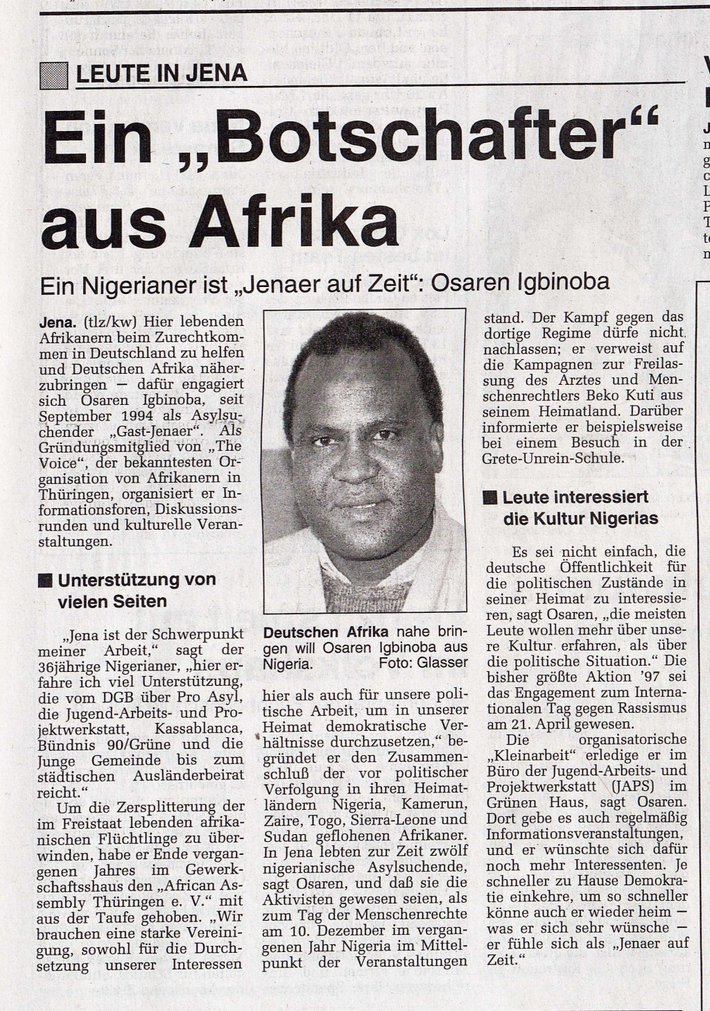

Osaren Igbinoba's commitment repeatedly aroused social and media interest.

Temporary Jenaer

Contrary to what the Thüringische Landeszeitung reported on 1 May 1997, Igbinoba did not remain a „guest Jenaer“ or „temporary Jenaer“, but became a long-time local political activist. He continuously drew attention to the rights of migrants and the connection between displacement and (post-)colonial relations of exploitation.

Local newspaper coverage in the early 1990s makes it clear that Osaren Igbinoba was an active and politically active person. He also criticised the fact that many Germans were more interested in the culture of his country of origin than in the country‘s political situation.

Nigeria was subject to a military dictatorship until the end of the 1990s, which could mean imprisonment, torture and death for human rights activists. To protect people who had fled to Germany from the political regime there, he and other migrant activists campaigned against deportations and a restrictive asylum law:

[...] in the face of „abuses in the hostel in the forest“ [...]

The Voice's multifaceted commitment was repeatedly supported by other initiatives, associations and organisations. In the 1990s, the Junge Gemeinde Stadtmitte (Young Community), members of the trade unions, the Foreigners' Advisory Council (as it was called at the time), the Foreigners' Commissioner and the Refugee Council, among others, actively campaigned for the rights of migrants and took a stand against racism and right-wing violence. But also people who were involved in the welfare associations or in social work tried to improve the concrete living conditions of migrants.

One of the issues that The Voice, together with other activists, brought to the media in order to generate social pressure and thus contribute to changing the situation, which was seen as problematic, was the accommodation in the reception centre in the forest, which had been the subject of fierce struggle in Jena since 1992.

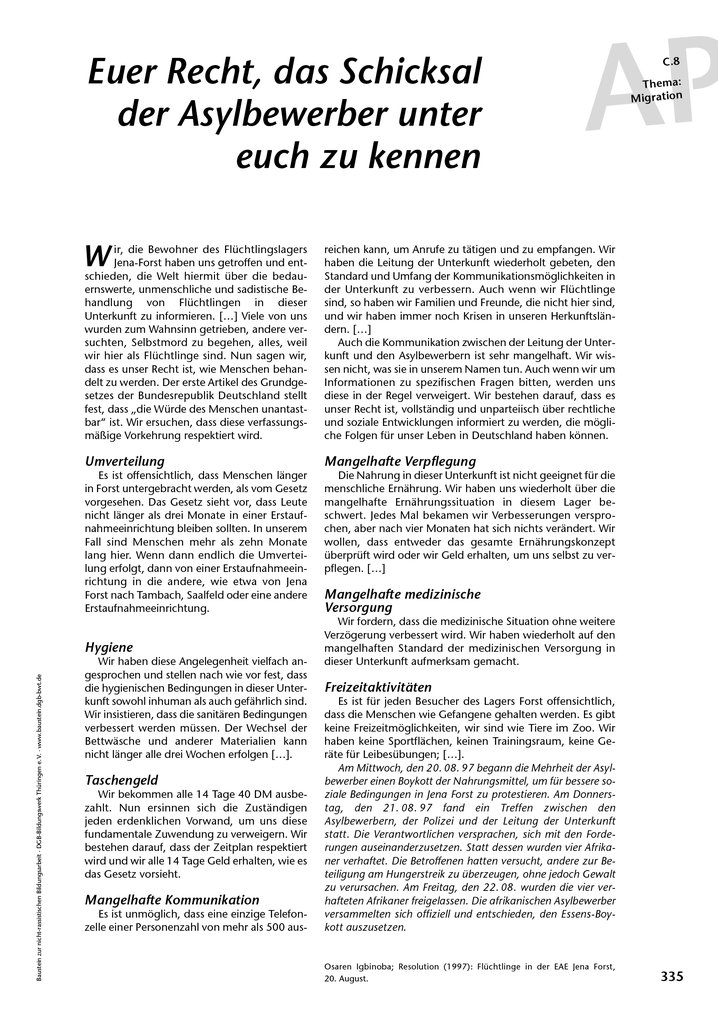

The activists criticised the living conditions and the social and political isolation of the people housed there. The Voice also supported and participated in a boycott and strike actions. For example, in August 1997, some asylum seekers in the forest went on hunger strike and drew up a list of demands. In a resolution they published during the hunger strike, the activists expressed their desperation. Some had already been driven to madness and suicide by the hopelessness.

In addition to criticising the asylum system, which criminalised people who had to flee, they made basic demands. Among other things, they demanded a bus connection between the forest and the city centre as well as improvements in hygienic conditions. The desire to cook for themselves - and thus live out existential human needs - was also part of their demands.

Resolution of the refugees in the initial reception centre, Jena Forest, 20 August 1997.

In 1998, The Voice also participated in the Refugee Caravan, which was organised by a nationwide network of activists and subsequently travelled through 44 German cities to draw attention to the rights of migrants and refugees.

A major supra-regional campaign by The Voice took place in 2000: As part of another caravan, The Voice invited refugees and activists from all over the world to a congress at Jena University. It was the first meeting of its kind in Germany.*

For those asylum seekers who wanted to travel from other places in Germany, this was associated with the risk of imprisonment due to the so-called Residenzpflicht (residential obligation), which was politically extremely controversial. This prohibited asylum seekers from moving beyond a predefined radius from the place where they were accommodated.