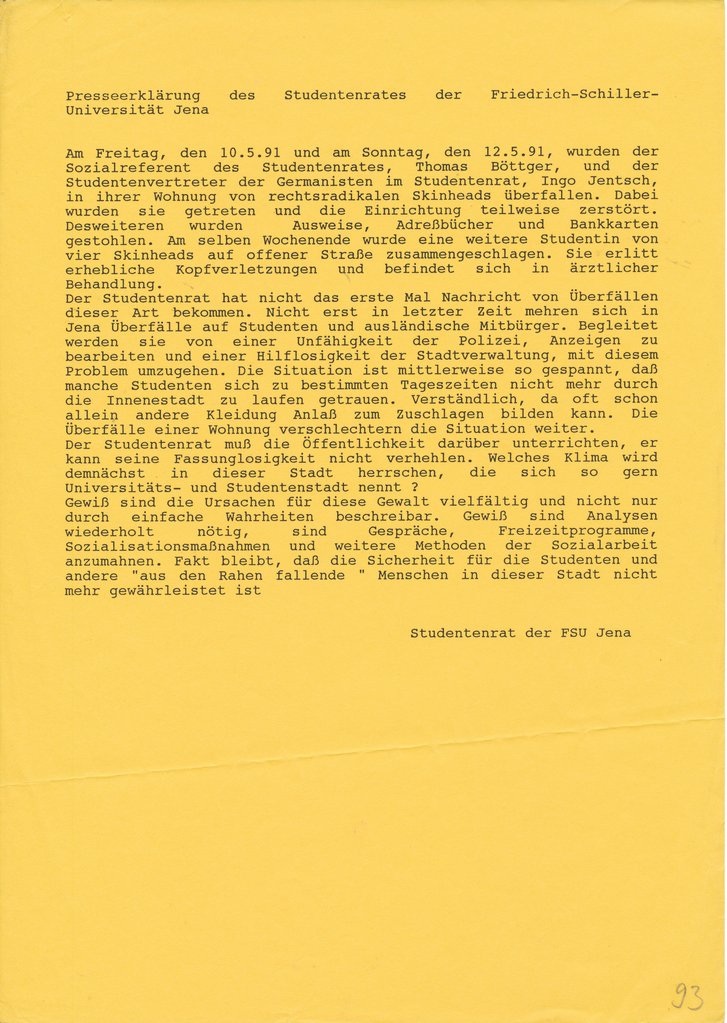

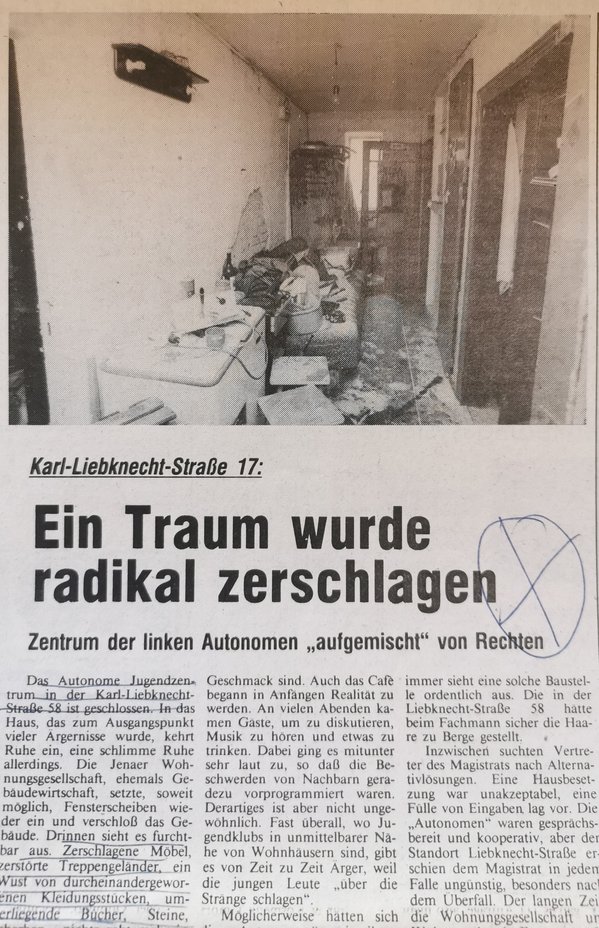

The squat in Karl-Liebknecht-Straße was uninhabitable after the break-in in May 1990. The residents had to move into emergency housing in the Kassablanca for several months. To protect them from further attacks, wooden wedges were kept there so that the doors could be quickly barricaded from the inside. In an interview for the website www.zweiteroktober90.de, a former resident of Karl-Liebknecht-Strasse 58 who was 18 at the time retrospectively recounts the night of 2-3 October 1990:

We had agreed for 2 October that we would go to the Kassablanca. There we communicated via radio with people who were on the road and looked where which gatherings were, where which groups moved to and how. But we knew that we could not defend the whole area. We just had to limit ourselves to controlling important objects and not letting anyone in. [...]

I think they went to East Jena and then to Kassa or the other way around, I don't know exactly. I think they came to the Kassa afterwards. But the Kassa was always very well defended. We had a nice foyer where the cloakroom was. There was a large closet as a drop-off point for the cloakroom. Our truncheons were in there. As soon as the alarm was raised, so to speak, people came to the cloakroom and didn't pick up their clothes, but a club. Then they went out and sorted it.

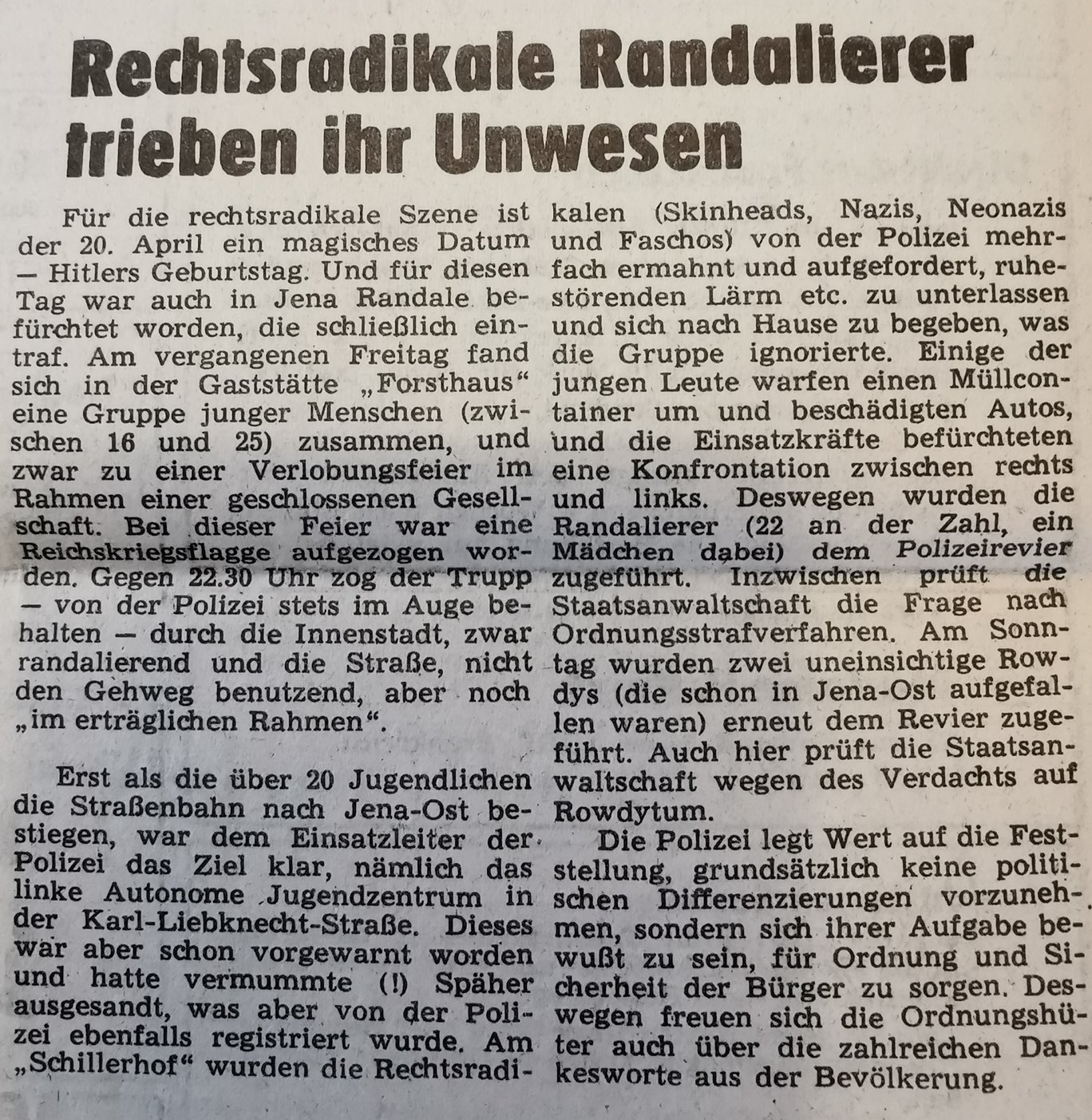

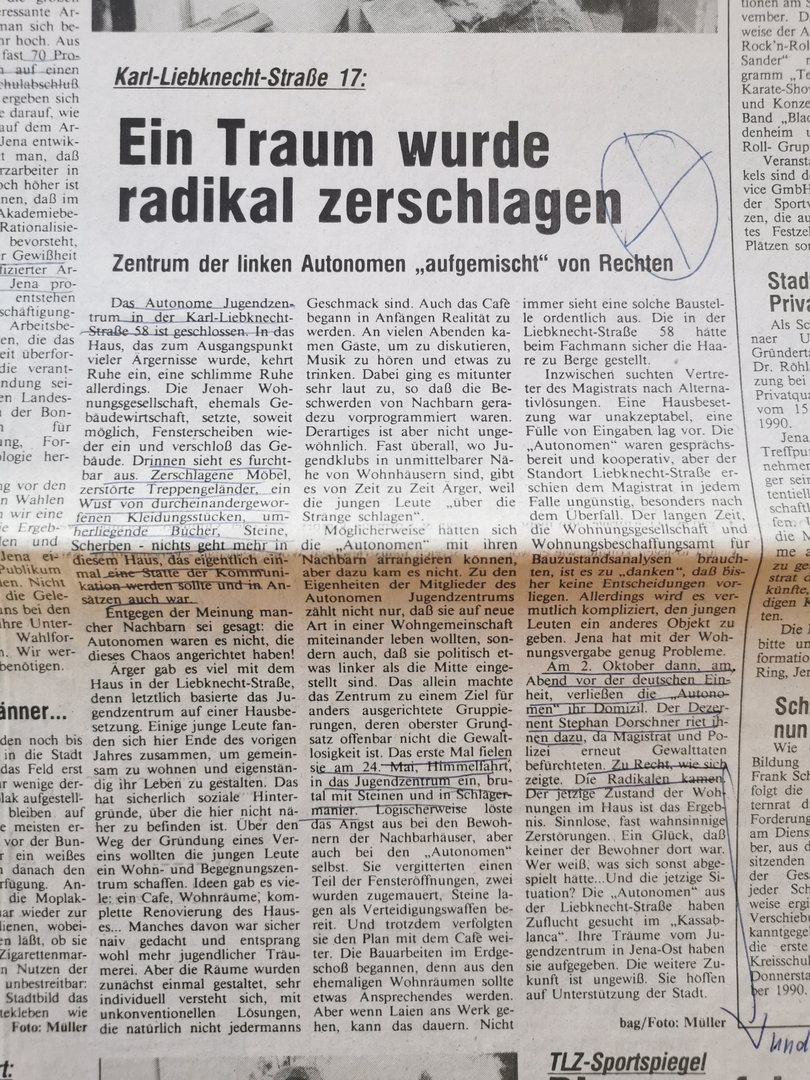

Thüringische Landeszeitung (TLZ), 23 October 1990