Uwe Böhnhardt, Uwe Mundlos, Beate Zschäpe, Ralf Wohlleben and other later members and supporters of the NSU grew up in Jena. During the GDR era, they were already active in various alternative youth scenes, especially in the right-wing skinhead scene, the so-called „Naziskins“. This scene grew in the late 1980s: in 1988, the State Security (Stasi) in Thuringia already counted more than 100 skinheads, although the number of unreported cases is likely to be significantly higher.*

In addition, the security authorities noted an increase in brutality as well as an increasing „glorification and imitation of fascist symbols and organisational structures“ in public.* Between March and June 1989, the Stasi in the district of Gera, which included Jena, noted „unusual incidents of neo-fascist content“ at schools on several occasions, primarily among students in the 8th and 9th grades.* However, problems with neo-Nazis in the GDR were always denied by officials: The authorities and the media rather portrayed them as apolitical „hooligans“.

Uwe Mundlos‘ former teacher describes how his radicalisation from the 8th grade onwards passed his teachers by, despite his short-cropped hair, combat boots, and frequent provocations. According to the teacher, he always „tried to keep politics [...] out of the classroom“ and only „marginally noticed“ Uwe's development. What the students did in their free time was, after all, their „private affair.“*

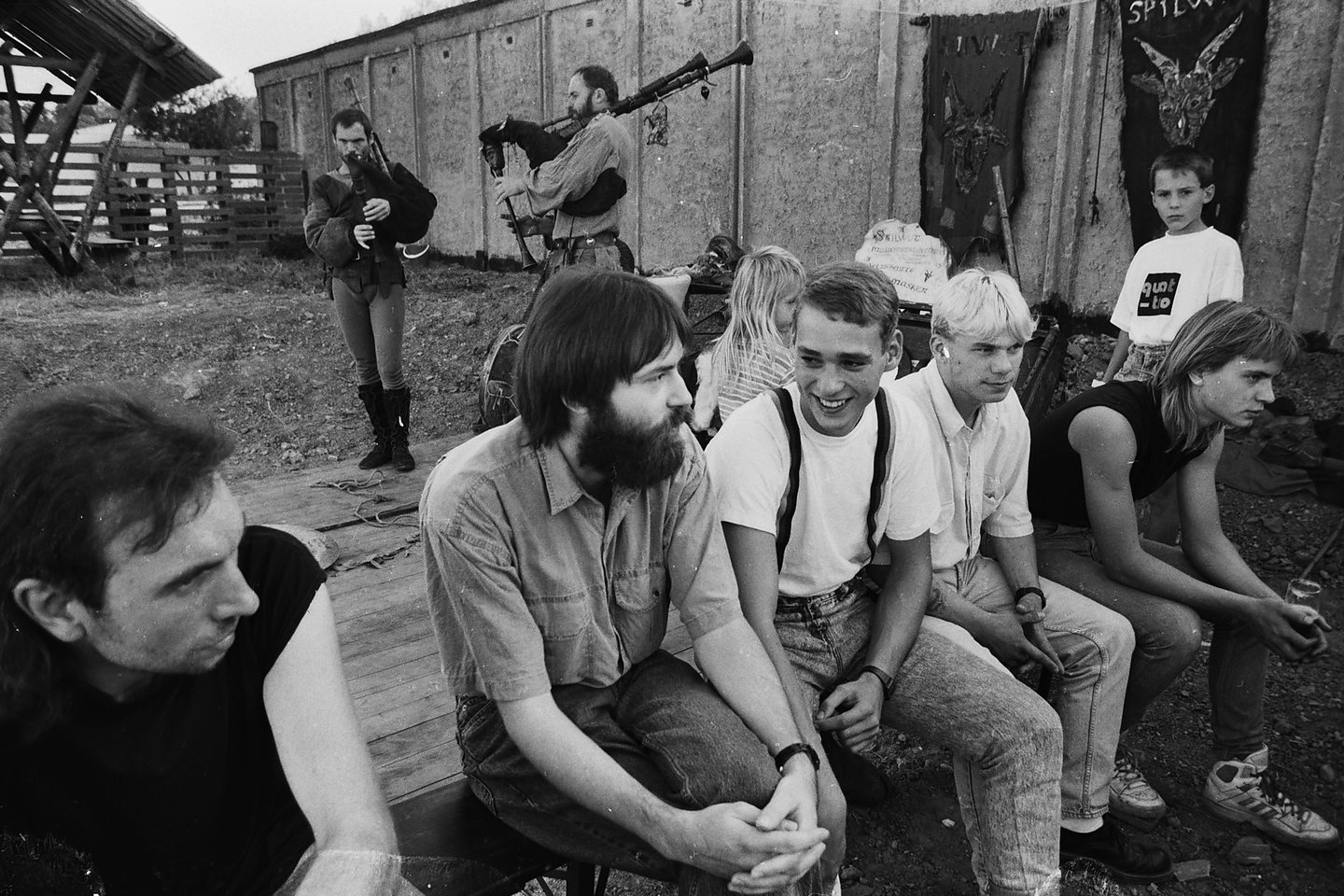

From 1990, the right-wing scene enjoyed new freedoms. Right-wing magazines and texts now became accessible to the later core trio, as did music by West German neo-Nazi bands such as Noie Werte, but also by the band Landser, founded in 1991, whose roots lay in East Berlin. The Winzerclub in Jena-Winzerla, which opened in 1991, became a meeting place for the right-wing scene: a free space for young neo-Nazis, who at the same time turned the area around the club into a fear zone for migrants and leftists.

Uwe Mundlos (centre) at the opening of Winzerclub, September 1991, private collection/photo: Frank Döbert

A short time later, Mundlos, Böhnhardt and Zschäpe became members of the Kameradschaft Jena (Jena Comradeship). From 1996, this belonged to the Thüringer Heimatschutz (THS), a network of right-wing extremist and militant groups with about 170 members (as of 2001), in which the „question of violence“ was openly discussed.

At the same time, the THS represented the link between the local, informal comradeships, the NPD and the nationwide neo-Nazi scene.* The trio began committing thefts and collecting weapons, which is why they were investigated several times in the 1990s. At the same time, a whole series of right-wing „initiatives“ began in Jena and the surrounding area.

Torsten Hahnel was a member of the punk scene at the time. Today he works for the registered society Miteinander e. V. (Together) in Halle and described the situation in an interview like this: