In the 90s self-defence was part of the everyday, partly also attacking Nazis. That is an important point, psychologically, I think, to be able to defend oneself […]. And that was so at the time too, luckily. I knew I could defend myself, but I was never violent, I never started a punch-up myself and was never interested in masculine rituals […].

Original soundbite Torsten Hahnel

Young Community (Junge Gemeinde) City Centre

Outreach and Antifascist Self-Organisation

In the early 1970s, individual pastors in the Protestant churches in the GDR started „Offene Arbeit“ (Open Church) outreach sessions, which became a shelter for youths who did not fit in. The target group included „the conspicuous, the vulnerable, the off-track“ and offered a „'space where you can be who you are, an open door, a conversation without condemnation"“ for young people that had been stigmatised by the SED (Socialist Unity Party) regime.*

The basic idea of Open Church was to accept young people and give them space for self-development, for „articulation and realisation.“* Walter Schilling, a pastor in Braunsdorf near Saalfeld and pioneer of Open Church in Thuringia, spoke retrospectively of „acceptance of the unacceptable,“ which for him meant „taking the individual young person as he is and not immediately pointing a finger or trying to bend him into shape.“*

A space was created in which young people could listen to their own music, be themselves, and meet like-minded people, a space in which they could party carefree, but also voice personal problems and their critical perception of SED politics. Young people contributed their own ideas to different event formats, helped shape the Open Church programme and learned to take on responsibilities.

Punk concert in the Junge Gemeinde Stadtmitte rooms with the punk bands Spermacombo and Ulrike am Nagel in April 1989

As a safe space, Open Church attracted youth subcultures that did not conform to the social norm, who did not want to conform, and who thus experienced exclusion and criminalisation by the authorities.

In addition to the blues scene and the punk scene, whose fans found freedom in Open Church, young people in the GDR had also taken to the skinhead subculture from the early 1980s onwards. However, since the 1970s, parts of the international skinhead movement had become radicalised and started espousing racist, neo-Nazi attitudes, which they acted out violently.

Right-wing Attacks in the GDR

In the 1980s, right-wing skinheads in the GDR also violently attacked migrants and dissidents. In Jena, an Open Church workshop with several punk concerts that took place at the Junge Gemeinde Stadtmitte in June 1987 ended in a confrontation between punks and violent skinheads.* In the entrance area, opposite a larger group of punks, a small group of skinheads started a fight with a punk from Halle.

Oh leave them alone, they’re stupid

In an interview about the clash with right-wing skinheads at the Young Community workshop "frei-zeit-los" (free-time-less) in June 1987, former punk Torsten Hahnel reported:

The punk was able to fight back. However, the example demonstrates the perceived superiority and dominant behaviour of the skinheads, who were already confident enough to appear as a group at that time, more than two years before the political system change in the GDR.

In reaction to the right-wing radical violence, the first independent antifascist groups were founded in Potsdam and Dresden in 1987. In the spring of 1989, another antifa group formed in East Berlin in the Church from Below, which began publishing an Antifa Info Sheet in July 1989 and reported on radical right-wing attacks, as well as on racism and xenophobia in East German society.*

Antifa Info Sheet produced by Open Church / Church From Below, East Berlin, July 1989

Rightwing motivated attacks on the Young Community safe space

Once the antifa’s first organisational structures had been put in place in Jena at the end of 1989, the local Autonome Antifa (Autonomous Antifa) set up weekly meetings in the rear building of Johannisstraße 14 and posted an advert in the Thüringische Landeszeitung (TLZ) newspaper in January 1990.*

Its aims were clear from its self-introduction in the TLZ: it wanted to educate and inform the public on right-wing extremism, to undertake prevention work and to provide advice for victims of right-wing extremist violence. In so doing, the antifa highlighted the existing lack of provision.

Autonomous Antifa’s announcement about the weekly meetings in the Junge Gemeinde rooms in Jena city centre, January 1990

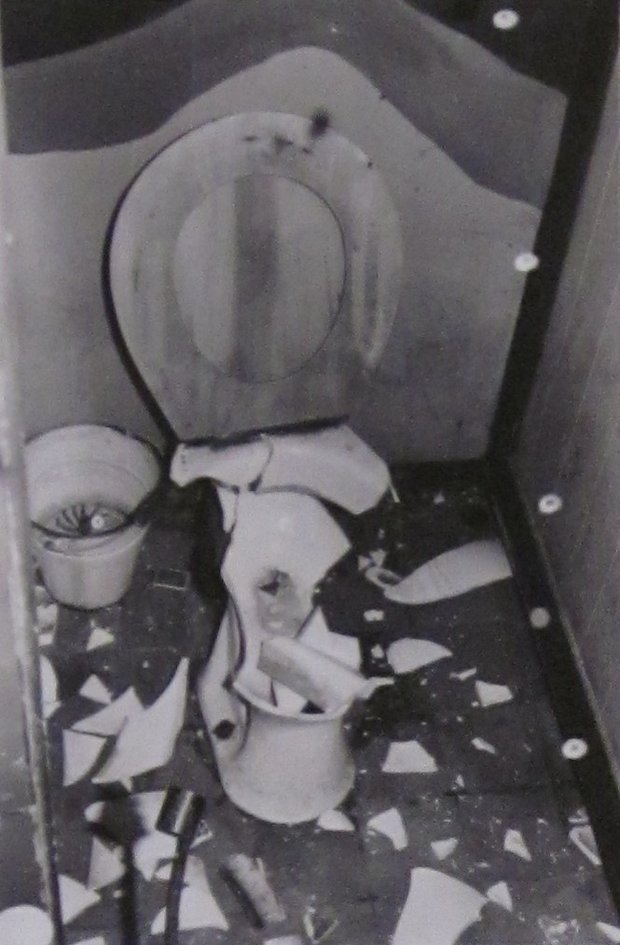

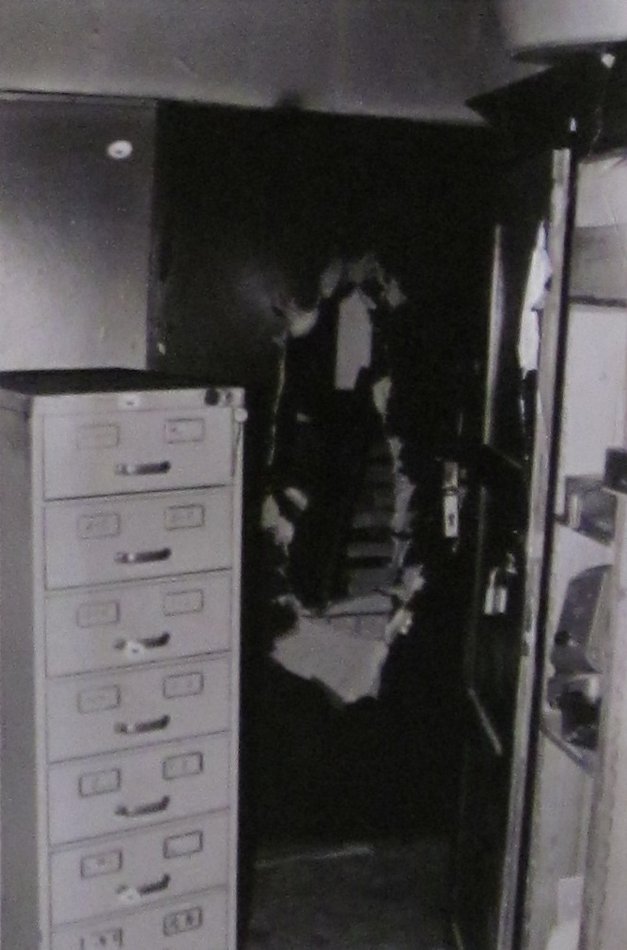

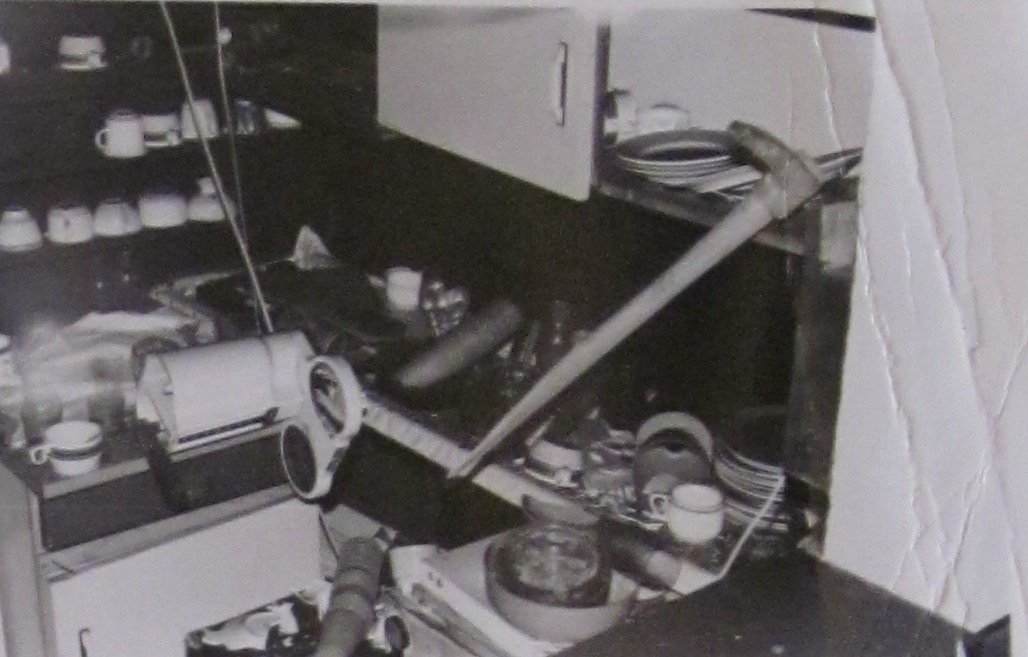

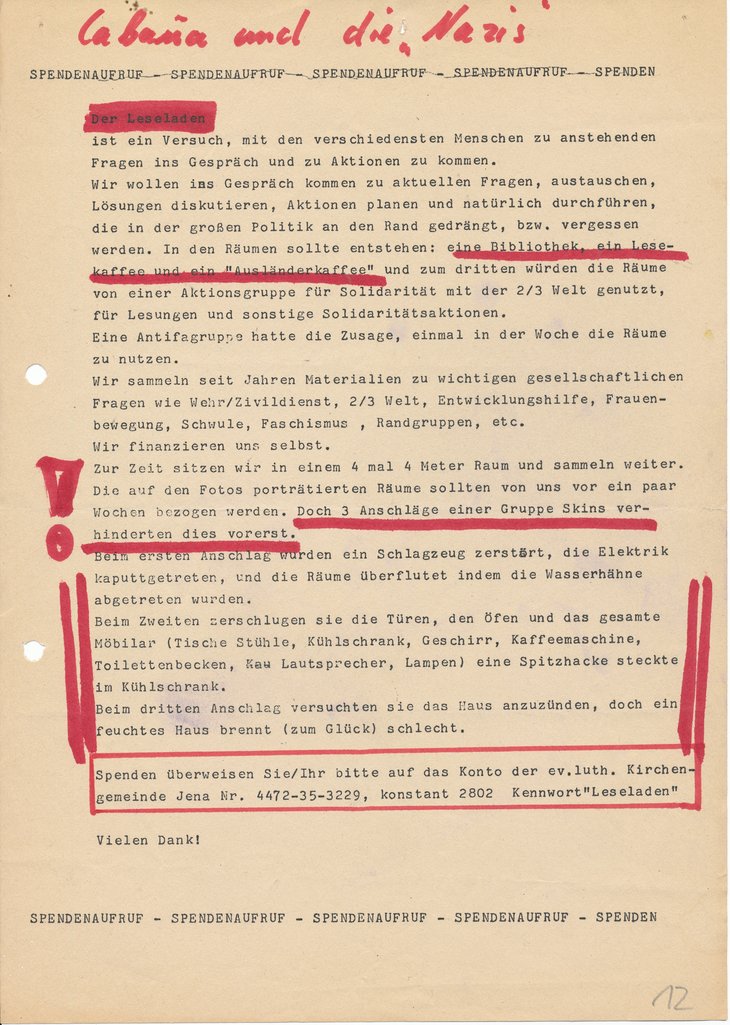

Presumably as a reaction to the antifa’s use of the rooms and to the fact that an „international café“ was to be set up in the space, the Young Community in the city centre was targeted by right-wing violence several times in early 1990 for providing a shelter for political dissidents. In the course of three right-wing motivated attacks, the offenders destroyed the facilities and caused water damage. The extent of the damage can be seen in three images from March 1990.

Destroyed furniture in the rooms of the Junge Gemeinde Stadtmitte after three attacks by right-wing skinheads, spring 1990

We were supposed to move into the rooms shown in the photos a few weeks ago, but three attacks by a group of skins prevented us from doing so for the time being. In the first attack, they destroyed a drum kit, stamped on the electrics and flooded the rooms by kicking the taps off. In the second attack, they smashed the doors, the ovens and all the furniture [...], a pickaxe was wedged in the fridge. In the third attack, they tried to set the house on fire, but (fortunately) a damp house doesn’t burn very well.

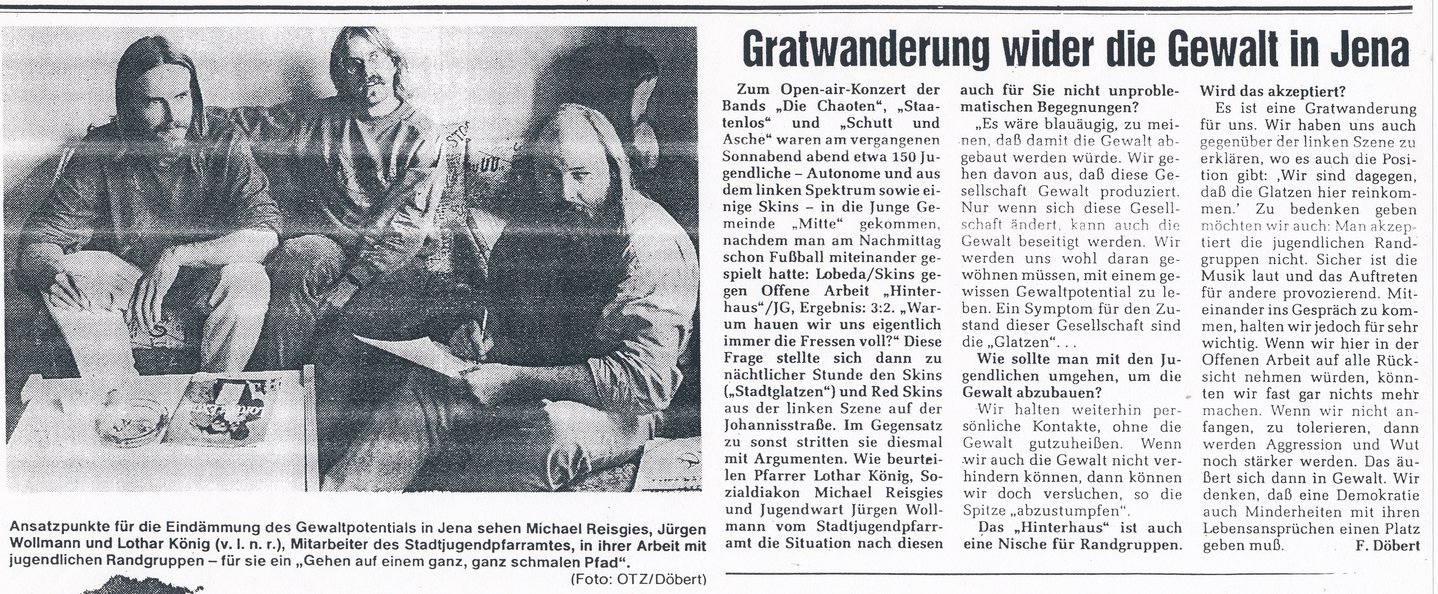

Although the Young Community in the city centre resumed its work in October 1990 with the city’s new youth pastor Lothar König, youth worker Jürgen Wollmann, and social deacon Michael Reisgies, the rear building needed a lot of work and was not back in use again until 1991.

Dealing with right-wing extremist youths

Much like the youth centres, which were formerly run by companies and mass organisations but had been transferred to municipal ownership during the system change, the Young Community in the city centre was also faced with the question of how to deal with right-wing extremist youths. In 1990, these had a greater presence in the city than in 1989.*

In 1991, the city’s youth pastor Lothar König, the social deacon, and the youth worker for the district church were still trying to mediate between young people who saw themselves as „right-wingers“ and „left-wingers“. In the summer and autumn of 1991, they organised football matches between skinheads from Lobeda and young people from the Young Community. The Ostthüringer Zeitung (OTZ) reported on this in several articles and quoted the staff of the city youth parish office on 2 October 1991:

The young fringe groups are not widely accepted. [...] However, we think it is very important to talk to each other. [...] If we don't start tolerating one another, then aggression and anger will grow even stronger. This will then turn into violence. We believe that a democracy must also create space for minorities and their way of life.

The City Youth Parish Office rejected this approach in early 1992, as Lothar König described in an interview in 2001* :

We just had a football match there with the Skins or 'Baldies', as I called them. [...] In '92, on 4 January, two of our members [...] were beaten up so badly that they could have been dead. And so then the time for football games was over.

Original soundbite Lothar König

So, in early 1992, the Young Community in the city centre took the decision not to pursue the path of mediation between „right-wing“ and „left-wing“ youths any further.

Attacks on political dissidents’ housing and cultural projects

Attacks on members of the Young Community in the city centre and their spaces were accompanied by numerous other violent attacks by right-wing radicals on political dissidents and people from migrant communities. On Ascension Day, 24 May 1990, an occupied house in Karl-Liebknecht-Straße 58, where an autonomous youth centre had been established, was attacked. Right-wing radicals deliberately forced their way into the space where left-wing youths had set up living quarters and a café.

A visitor who photographed the departing attackers had to flee across the roof of the house when the neo-Nazis noticed his camera and returned to the house. The photos document the attackers approaching, armed with baseball bats, and the photographer’s escape.*

Neonazi attack on the occupied house in Karl-Liebknecht-Strasse 58, and the photographer’s escape over the roof, 24 May 1990

Where is the roll of film? Where is it?

Ulf Launhardt, who was visiting the Karl-Liebknecht-Straße 58 at the time of the attack on 24 May 1990, retrospectively reports:

Und dann kamen die mit diesen Baseballknüppeln zu mir hoch: „Wo ist der Film? Wo ist der Film?“. Da habe ich gesagt: „Hab ich nicht.“ Hatte ich keinen drin. Das gipfelte dann darin… Die hatten hinten an der Seite so eine Terrasse. […] Und irgendwie ging´s da hinten aus dem Fenster und da war wie so eine unfertige Dachterrasse oder so. Da bin ich rauf und das ist das Dach vom Nachbarhaus und da hing ich am First, am Dachfirst und hab dann mit der Baseballkeule eine auf die Finger bekommen, weil ich den Film nicht rausgegeben habe.

Original soundbite Ulf Launhardt

Unlike in the areas Lobeda and Winzerla, there were plenty of safe spaces in the city centre for politically opposed young people in the form of the Young Community, the Autonomous Youth Centre and the Kassablanca. However, these were fragile and could become fear zones when attacks by right-wing radicals occurred. Those affected by right-wing violence had no choice but to defend their spaces and re-establish safe spaces on their own.

The city centre [...], that also became dangerous on Tuesdays after ten pm...

Even Johannisstraße, a public space in the middle of Jena's city centre, became a fear zone at certain times in the early nineties, as described by the daughter of the former city youth pastor Lothar König...

...Katharina König-Preuß, a member of the state parliament for the party DIE LINKE, member of the Thuringian investigation committee on the NSU, and activist against right-wing extremism, in an interview in DIE ZEIT in April 2019:*

It was a normal occurance in Jena that people who were attributed to the alternative scene were attacked on a weekly basis. And every week there were the reports: Who was attacked, who was beaten up, who had something happen to them, who was in hospital? Every week! The city centre, where we could still move around more or less normally, also became dangerous on Tuesday evenings from ten o'clock onwards, because Nazis in cars with baseball bats were waiting in the streets and looking: Are there people from the Young Community coming? Then we would slowly follow their cars to a darker street and catch them. We knew the number plates off by heart.

Text: Katharina Kempken